Have you ever wondered what happens to the toilet water after you flush? Or where your shower water goes? This water, along with the water from your washing machine and sink, is called ‘wastewater', and it flows through your home piping into either a septic tank or all the way to a wastewater treatment plant. Because wastewater contains feces and other contaminants, it is essential for it to be treated before it can be discharged into nearby lakes or rivers.

What’s In Wastewater?

Human feces mostly contains dead cells and undigested food, but it’s also filled with tons of dead and alive bacterial cells and viruses. However, as one would suspect, not all fecal matter is the same. The feces from a person with a disease will likely contain infectious bacteria or viruses. With this in mind, imagine a scenario in which a widespread viral disease affecting millions of people was detectable through human stool. In this scenario, a neighborhood sewage system would contain a plethora of genetic material that could be used to monitor the progression of the disease.

This scenario isn’t too far from reality. In fact, this is what researchers and institutions from around the world have done for more than two years since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. By testing wastewater, which contains human waste, researchers are able to monitor the peaks and troughs of SARS-CoV-2 in high-risk, urban areas. Furthermore, by using this method researchers can predict trends in infection rates since infected individuals typically undergo viral shedding before symptoms appear.1 The identification of a sharp increase in viral signatures detected in wastewater could indicate the possibility of a spike in positive COVID-19 diagnoses, as well as an increase in hospitalizations. This information could be extremely beneficial for healthcare professionals to better prepare for an influx of patients and reduce the risk of overwhelming healthcare systems.

Early Detection of Variants Using Wastewater

Besides predicting trends in community infection rates, another significant role that wastewater monitoring has played is in the early detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Using wastewater, researchers successfully detected Alpha, Delta, and other early variants roughly two weeks before appearing in clinical testing.2 Similarly, the original Omicron variant in San Diego was detected in wastewater a week before it showed up in clinical sampling.2 Because of these advantages, wastewater testing for SARS-CoV-2 was rapidly adopted. Indeed, the number of survey sites exploded from only 38 in October 2020 to approximately 3,600 in September 2022, involving around 280 universities, and spread across 70 countries.3

Want to hear more from Norgen?

Join over 10,000 scientists, bioinformaticians, and researchers who receive our exclusive deals, industry updates, and more, directly to their inbox.

For a limited time, subscribe and SAVE 10% on your next purchase!

SIGN UP

Luckily, wastewater surveillance is not just limited to SARS-CoV-2. The first documented case of wastewater being used to track a disease occurred in 1854 during the cholera outbreak in London.4 Since then, epidemiologists have used wastewater to track and contain diseases in the United States, such as polio as well as diseases caused by noroviruses and rotaviruses.4 Recently, Dr. Delatolla from the University of Ottawa detected monkeypox wastewater signals in Ottawa and Hamilton. Furthermore, researchers from Stanford University and Emory University who focus on monitoring monkeypox in wastewater picked up viral signals from two dozen locations across 10 different states.5

The Future of Wastewater Surveillance

Even with all its benefits, the future of wastewater surveillance still remains uncertain. It all boils down to funding. Researchers are concerned that as the threat of COVID-19 dies down, so too will government interest and funding. In Ontario, there are currently more than a dozen labs whose funding for wastewater surveillance ends in March 2023, and the researchers will be left wondering whether it will continue or not.3

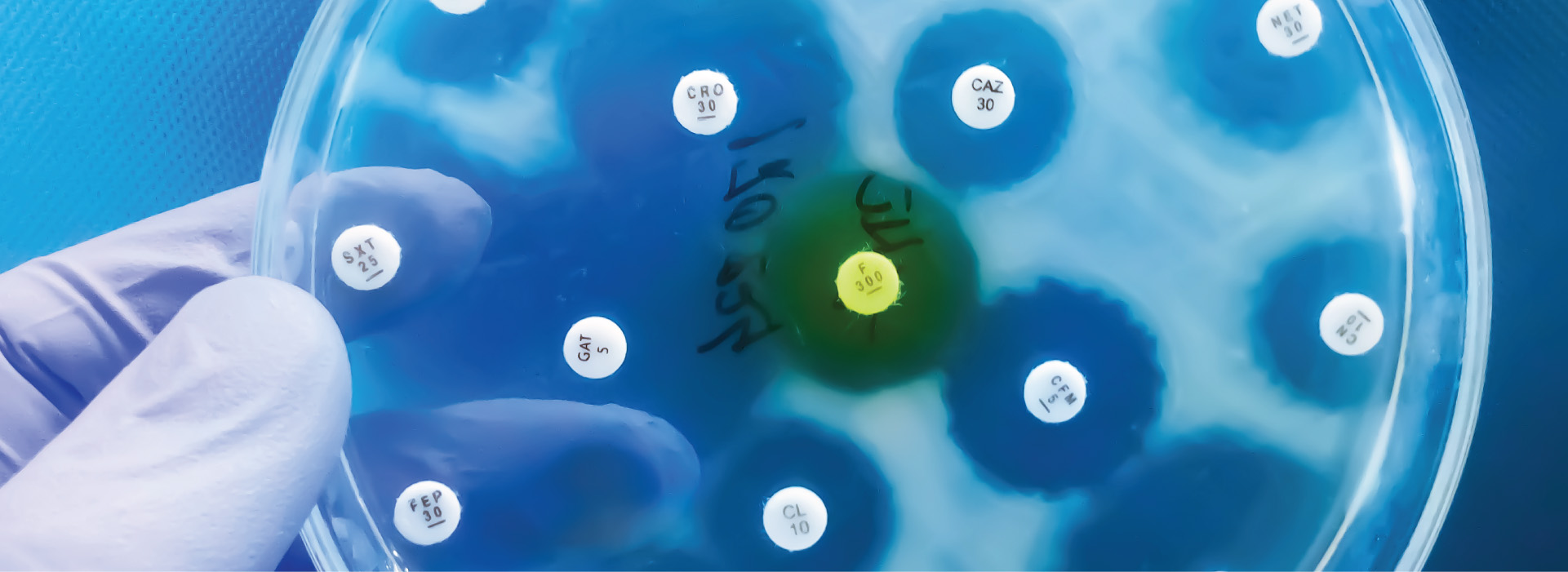

There is still, however, a glimmer of hope. At the federal level in Canada, officials have recognized the potential of wastewater testing not only for SARS-CoV-2, but also for other pathogens.3 As of October 2022, the national research team is monitoring 25 wastewater sites in 13 different Canadian cities for SARS-CoV-2 and monkeypox.3 In addition, public health officials are exploring the possibilities of monitoring antimicrobial resistance or diseases such as tuberculosis or influenza through wastewater.3 There are also ongoing efforts to set up a surveillance network between countries to detect viral signals early on in order to prevent future outbreaks. Researchers at Western University, in London Ontario, are working with teams in Uganda and India to collect and analyze wastewater from drainage systems and latrines.3

Coordinated global surveillance of wastewater has the potential to act as an early warning system with the ability to alert local healthcare authorities of an impending outbreak and warn the world of future pandemics. With ample evidence that wastewater surveillance systems work, we hope to see more funding for it in the future. If your research involves wastewater testing, check out our Soil RNA Purification Kit - Supplementary Protocol for Isolation of RNA from wastewater.