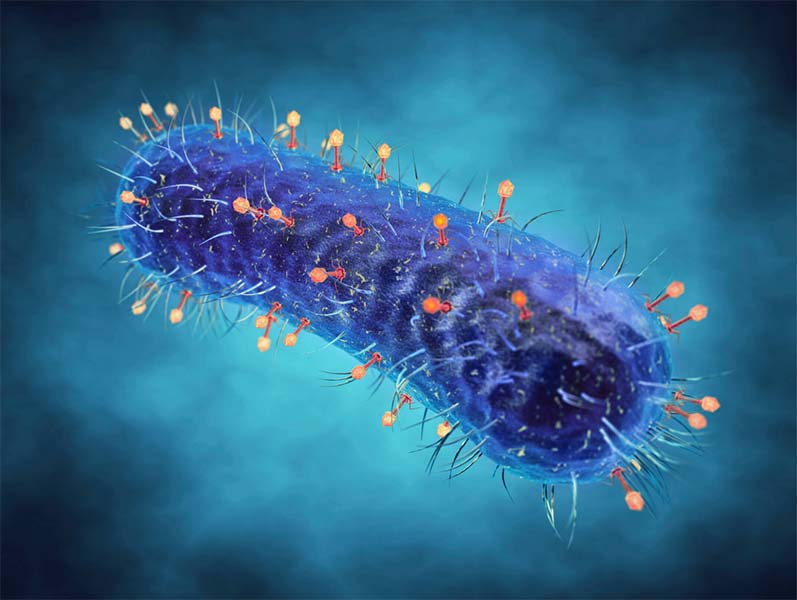

If you have a passing familiarity with biological sciences then you have probably come across the term phage or bacteriophage before. But what exactly do they do? The name itself gives us, or at least those of us that know a little Greek, a clue, as phage is derived from phagein, meaning “to devour”.1 Slap that together in a portmanteau with bacteria and you have something, a virus, that devours bacteria. While not strictly accurate as bacteriophages don’t eat per se, they still treat bacteria as prey. This is because the phage takes control of the bacteria’s internal mechanisms to make more copies of itself.2 From here, two different reproduction cycles may occur, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

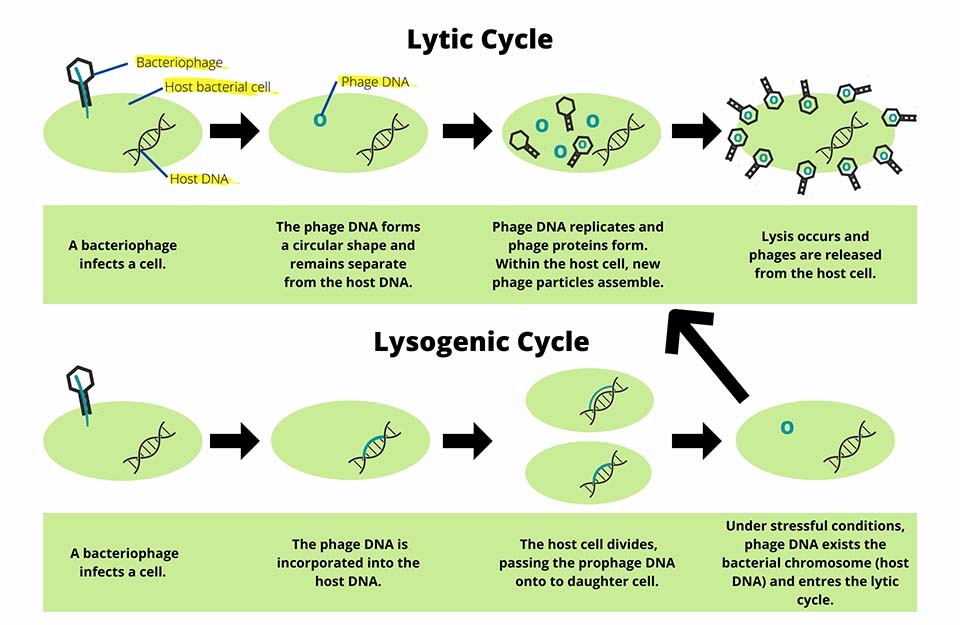

Reminiscent of an alien bursting from the chest of its host, in the lytic life cycle the phage replicates itself at a high rate until it eventually reaches a critical point where the host cell lyses open,

releasing the newly minted phages to go on and infect further bacteria.3

Some of these viruses take an even more insidious approach, the lysogenic cycle, incorporating themself into the host cell’s genome, forming an inactive prophage.3

This allows them to replicate alongside the cell without killing it, that is... until conditions are right.3

When an activating event occurs, such as DNA damage, the prophage separates itself and enters the lytic cycle.3

Now that we have a basic understanding as to what a bacteriophage is, let’s delve a little deeper into the science.

Reminiscent of an alien bursting from the chest of its host, in the lytic life cycle the phage replicates itself at a high rate until it eventually reaches a critical point where the host cell lyses open,

releasing the newly minted phages to go on and infect further bacteria.3

Some of these viruses take an even more insidious approach, the lysogenic cycle, incorporating themself into the host cell’s genome, forming an inactive prophage.3

This allows them to replicate alongside the cell without killing it, that is... until conditions are right.3

When an activating event occurs, such as DNA damage, the prophage separates itself and enters the lytic cycle.3

Now that we have a basic understanding as to what a bacteriophage is, let’s delve a little deeper into the science.

NORBLOG

Want to hear more from Norgen?

Join over 10,000 scientists, bioinformaticians, and researchers who receive our exclusive deals, industry updates, and more, directly to their inbox.

For a limited time, subscribe and SAVE 10% on your next purchase!

SIGN UP

The Science:

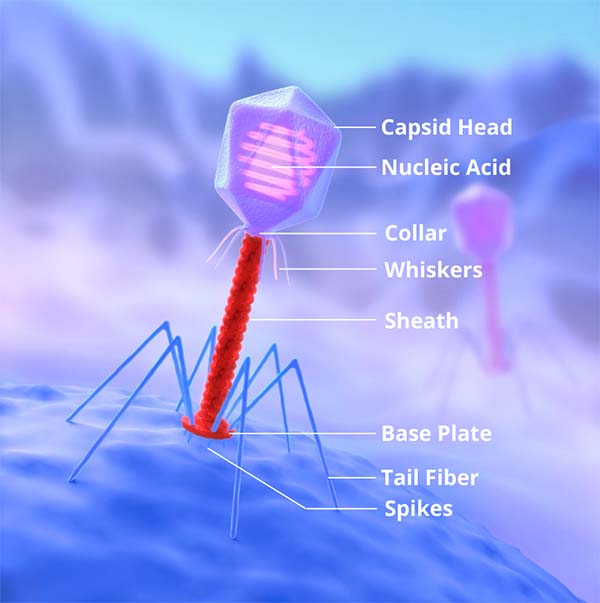

Phages, at the most basic structural definition, are composed of a protein capsid surrounding a strand of genetic material, either DNA or RNA.

At a slightly higher resolution view, phages can be broken up into three main groups by structure: icosahedral, which is in essence just a geometric blob, filamentous (shaped like a hair) and head-tail.4

This last group is what most of you are likely familiar with: the strange, robotic alien-like figures with legs, a body and a head.

The poster child for phages, the T4-bacteriophage, falls into this category.

Phages, at the most basic structural definition, are composed of a protein capsid surrounding a strand of genetic material, either DNA or RNA.

At a slightly higher resolution view, phages can be broken up into three main groups by structure: icosahedral, which is in essence just a geometric blob, filamentous (shaped like a hair) and head-tail.4

This last group is what most of you are likely familiar with: the strange, robotic alien-like figures with legs, a body and a head.

The poster child for phages, the T4-bacteriophage, falls into this category.

For all three of these categories, infection begins with adhesion to the host cell and is done through the use of specific proteins.4 For the head-tail species, it is through the legs; for the filamentous species, it is through a set of string like proteins exuding from one end; for the icosahedral specimens, it is through surface spike proteins.4 Generally speaking, once the adhesion proteins attach to the surface of a host bacterium, another protein punches through the cell membrane into the cytoplasm, and injects the viral genetic material.4 However, some types of bacteriophages actually fuse their capsid with the host cell and deposit their genetic material into the periplasmic space, where it then penetrates into the cytoplasm.5 From there, depending on species and external factors such as degree of co-infection by other phages, the lytic or lysogenic cycle begins.

The Importance of Bacteriophages

Okay, cool. So now that we know what bacteriophages are, why do they matter?

Other than being a fascinating microscopic horror show, complete with all the hallmarks of an award winning scream fest including a tireless implacable monster,

phages play an important role in not only the environment but in science as well.

In nature, beyond the basics of predator/prey interactions, phages are strongly suspected to cause horizontal gene transfer.6

Okay, cool. So now that we know what bacteriophages are, why do they matter?

Other than being a fascinating microscopic horror show, complete with all the hallmarks of an award winning scream fest including a tireless implacable monster,

phages play an important role in not only the environment but in science as well.

In nature, beyond the basics of predator/prey interactions, phages are strongly suspected to cause horizontal gene transfer.6

Logically, this makes sense as the excision process when a prophage activates and separates itself from a host genome may very well take a little something extra with it,

which then reinserts on subsequent lysogenic infections.7

Gene transfer may also occur due to failed infections, as a portion of the viral genome is

incorporated into the host genome so the cell has a reference to help defend against future viral infections.7

Occasionally this can result in a bacteria acquiring antibiotic resistance, as virome studies have shown that they can carry resistance genes.7

In this same vein, there is a growing interest in using phages to combat the rising threat of antibiotic resistance in a process called phage therapy.6

A frightening concept is that of a post-antibiotic world, where a simple infection could be a death sentence if alternatives are not found.

As phages are an effective means of destroying bacteria, inoculating an individual suffering from an infection, or even as a preventative measure, could be the answer to this problem.6

In a slightly more abstract application, phages were found to be a useful tool for studying genetics.8

Mu phages in particular are of great interest to researchers as they copy themselves within the host genome through replicative transposition.8

This results in large rearrangements of the chromosome.8

By selectively mutating the phage to remove its lethality and inserting selectivity genes (kanamycin resistance, etc) and a Lac operon that lacks a promoter region, researchers can monitor gene expression.8

This occurs when the prophage inserts itself in the proper orientation and location to make use of a promoter region of another gene, as without it, the β-galactosidase and other proteins that the Lac operon encodes for will not be produced.8

Production of these proteins allows the cell to metabolise lactose into D-glucose and D-galactose.8 Thus, by monitoring for galactose production, researchers can tell when the genes are functional.8

As this is essentially an insertion mutation, the phage can then be screened for to determine its location and correlate it to the gene it inserted itself into.8

Due to its promiscuity it can be used to study polar mutations in any gene.8

In this same vein, there is a growing interest in using phages to combat the rising threat of antibiotic resistance in a process called phage therapy.6

A frightening concept is that of a post-antibiotic world, where a simple infection could be a death sentence if alternatives are not found.

As phages are an effective means of destroying bacteria, inoculating an individual suffering from an infection, or even as a preventative measure, could be the answer to this problem.6

In a slightly more abstract application, phages were found to be a useful tool for studying genetics.8

Mu phages in particular are of great interest to researchers as they copy themselves within the host genome through replicative transposition.8

This results in large rearrangements of the chromosome.8

By selectively mutating the phage to remove its lethality and inserting selectivity genes (kanamycin resistance, etc) and a Lac operon that lacks a promoter region, researchers can monitor gene expression.8

This occurs when the prophage inserts itself in the proper orientation and location to make use of a promoter region of another gene, as without it, the β-galactosidase and other proteins that the Lac operon encodes for will not be produced.8

Production of these proteins allows the cell to metabolise lactose into D-glucose and D-galactose.8 Thus, by monitoring for galactose production, researchers can tell when the genes are functional.8

As this is essentially an insertion mutation, the phage can then be screened for to determine its location and correlate it to the gene it inserted itself into.8

Due to its promiscuity it can be used to study polar mutations in any gene.8

The Future of the Phage

Phages are the scourge of the bacterial kingdom, hunting and infecting them in a plot that I’m honestly surprised hasn’t been turned into a C list Hollywood movie.

They have given us new insights into cellular machinery, provided tools to study genomes and protein expression, and even joined us in the war against disease as staunch allies.

Bacteriophages are certainly one of the marvels of the natural world.

If you want to study these microscopic wonders, Norgen Biotek has products for every step in your workflow, from collection to extraction to downstream applications.

Phages are the scourge of the bacterial kingdom, hunting and infecting them in a plot that I’m honestly surprised hasn’t been turned into a C list Hollywood movie.

They have given us new insights into cellular machinery, provided tools to study genomes and protein expression, and even joined us in the war against disease as staunch allies.

Bacteriophages are certainly one of the marvels of the natural world.

If you want to study these microscopic wonders, Norgen Biotek has products for every step in your workflow, from collection to extraction to downstream applications.